Tales Of The Past: A word about a word or two

By Ross Stanley

A chat about literary links to horses and racing.

The 1890s were both challenging and satisfying. Early on, the populace endured the economic woes of a Depression that also impacted overseas countries. At the end of the decade, the formation of the Commonwealth of Australia was on the cusp of being completed.

It had been a century since the English had started dumping their convicts and three quarters of the white residents were now native of a land that was first referred to as Terra Australis, a Latin term meaning South Land.

Centuries earlier, in the belief that there must be a yet-to-be-discovered land mass to balance that of the northern hemisphere, the word Incognita was present as well.

With respect to the push towards Federation, issues such as defence, trade, immigration and transport had convinced colonial minds of its value. Furthermore, there was a distinctive ethos that took care of the hearts.

The initial arrivals from the British Isles brought their folk music and poetic customs with them. Over time, the forms were flavoured with the uniqueness of their new and starkly different environments.

Of course at this time, there was no radio, television or commercially available recorded music. The “media” comprised words that were spoken, sung live or printed. Writing a Letter to the Editor in newspapers was the closest mechanism to contemporary offerings such as a posting on Facebook.

AN EMERGING HERITAGE

The Bulletin magazine was launched in 1880. J.F Archibald and John Haynes were the novel periodical’s key founders. Literary submissions were encouraged and the concept of a local identity set apart from the Mother Country's background was fostered. The weekly publication earnt the nickname of the Bushman’s Bible because out-of-towners could not access the dailies.

Archibald was a somewhat quirky character. The Victorian, who lived from 1856 to 1919, had a penchant for the French aspect on his maternal side. He changed his name from John Feltham to Jules Francois and his will directed that a fountain in his honour for Hyde Park in Sydney was to be designed by a French sculptor. There was also a bequest to fund an Archibald Prize for painted portraits.

The Bulletin’s existence ushered in halcyon days for bush ballads, a narrative genre involving metre and rhyme.

In 1885, Andrew Barton Paterson (1864-1941), began sending in successful contributions to the magazine. As an alias, he used “The Banjo”, a link to the family’s station horse that was raced.

Judging by his long list of occupations and exploits, the dyed-in-the-wool horseman, born near Orange in 1864, was always chomping on the bit. He was a solicitor, a war correspondent, an army officer in the Remount department in World War I, editor of the racing paper The Sydney Sportsman, poet, novelist and a broadcaster with the ABC.

For sport, Barty rowed, played tennis and rode with the Sydney Hunt Club, on polo fields and as an amateur jockey at Randwick and Rosehill.

During his childhood period at Illalong at Yass near the road between Sydney and Melbourne, he was stimulated by the sight of bullock teams, coaches and drovers in action. In various contexts, the feats of Murrumbidgee-Snowy riders that he witnessed underpinned his creative output. However his range encompassed all sorts of themes.

Paterson’s immersion in the turf world engendered an assortment of topics.

A Melbourne Wire account in 1896 coldly stated that “Richard Bennison, a jockey, aged 14, while riding William Tell in his training, was thrown and killed. The horse is luckily uninjured.”

Paterson responded in verse with Only A Jockey, a lament for the loss of a young, innocent life. In Our New Horse, he took a slightly humorous angle on the perils of owning a racehorse while Hard Luck was about a racetrack tout.

Some of his other scenarios were How The Favourite Beat Us, The Old Timer’s Steeplechase, A Dream Of The Melbourne Cup, A Rule Of The A.J.C. and The Amateur Rider.

The last two lines of Riders In The Stand express an age-old sentiment.

“You ride a slashing race, and lose, by one and all you’re banned!

Ride like a bag of flour, and win, they’ll cheer you in the Stand.”

His tribute to the stellar jumps jockey Tommy Corrigan is pithy.

“You talk of riders on the flat, of nerve and pluck and pace.

Not one in fifty has the nerve to ride a steeplechase.”

The words of Waltzing Matilda were written during Banjo’s stay near Winton in 1895. The lyrics were decisively couched in Australian lingo with jumbuck, coolibah, billabong, billy and tucker set to baffle future visitors to these shores.

Angus & Robertson published Paterson’s The Man From Snowy River, and Other Verses in October 1895. The title poem had been a real hit when it first appeared in April 1890. The book’s first edition sold out in a week and, after a few months, the tally was 7,000.

In 1939, Paterson was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for his contribution to literature. After a brief illness, Barty passed away in 1941.

THE BREAKER AND OTHERS

The role of Clancy of the Overflow in the 1982 movie based on The Man From Snowy River was played by Jack Thompson, the true-blue fan of bush ballads who made compact discs (CDs) of his readings of Paterson’s work.

The consummate Australian actor was also cast in the 1980 film Breaker Morant as Major James Francis Thomas, the defence counsel for Harry Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton in their 1902 war crimes court martial during the Second Anglo-Boer War in South Africa.

The three lieutenants were found guilty of murdering 12 prisoners. Moran and Handcock were executed while Witton was freed after four years of a life sentence.

Morant’s “Breaker” tag traced back to his artful training of brumbies.

Who’s Riding Old Harlequin Now is an absorbing, reflective and nostalgic ballad that graced a page of The Bulletin in 1897.

All up, The Breaker byline was attached to some 60 bush ballads the journal published.

He was a conjuror of controversy. His claim to be of upper crust heritage was hotly denied. He is thought to have been Edwin Henry Murrant (probably1864-1902).

After travelling from England to Townsville in 1883, “Breaker” pursued an itinerant lifestyle for 16 years. He spent a year with the South Australian Mounted Rifles squad when the South African hostilities broke out in 1899.

Morant then returned to his birth country briefly before going back in 1901 to fatefully team up with the Bush Veldt Carbineers in their tussle with Boer guerilla soldiers.

A summary about Harry placed on the record by his friend A.B. Paterson said that “he can do anything better than most people, can break in horses, trap dingoes, drive cattle, play polo, dance, sing, run, fight, talk, drink and borrow money”.

The Scotsman Will Ogilvie (1869–1963) was another in the mould of horseman-poet. He was attracted by the poetic products of Adam Lindsay Gordon and had his father George’s approval to go to Australia.

Young Ogilvie went by Cobb and Co from Sydney to a pre-arranged sojourn at Belalie near Bourke in 1889.

According to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, “he was wholly captivated by the outback and for twelve years roamed from the Channel country of Queensland to the Coorong of South Australia. Horse-breaking, droving, mustering and camping out on the vast plains became the salt of life to him. As he wrote in My Life in the Open (London, 1910), the Australian bush 'has a peculiar witchery of its own … that spell that brings the drover and traveller back again and again to worship at the shrine of its silent beauty; that charm that chains the true bushman to his love though half the world lies between’.”

Ogilvie became a prolific supplier of poems to The Bulletin and other organs. Even though he returned to Scotland in 1901, he pressed on with sending poetry to The Bulletin. His The Australian and Other Verses was released in Sydney in 1916.

The Hoofs Of The Horses captures Will’s passion for the potency, excitement and pleasure that the animal exudes while A Gallop From The Train is a daydream about hunting on a grey that was triggered whilst gazing out of a carriage window.

Another leading figure in Henry Lawson (1867-1922), renowned for his realistic short stories, focussed mainly on non-equine topics. An exception was Dan Wasn’t Thrown From His Horse.

Clarence Michael James Stanislaus (C.J.) Dennis (1876-1938) was a poet and journalist famously known for The Sentimental Bloke, the love story that received international acclaim as it brightened the gloom of World War I.

The South Australian son of Irish parents dabbled with verse about the thrills of Melbourne Cup week with Galloping Days and Galloping Horses.

Arthur Hoey Davis (1868-1935 ), who first saw light of day at Drayton near Toowoomba, was the eighth of 13 children. His father Thomas had completed a blacksmith-farrier apprenticeship in Wales. Arthur’s teenage job was that of a stockman at nearby Pilton, an experience that ensured he was hooked on horses. Later on, he was regarded as a top class polo player.

When Arthur accepted clerical responsibilities in Brisbane, he took up rowing and wrote a column for Brisbane’s Chronicle under the pseudonym of Steele Rudd. The first word was the name of an English essayist. The surname was derived from a part of a boat.

Thomas, his Irish wife Mary, and their flock lived on a selection at Emu Creek. Events there and other ideas shaped the basis for Rudd’s short stories about Dad, Mother and their children Dan, Joe, Dave, Joe, Kate, Sarah and Norah.

The first chapter, which was a hit, was printed in 1895 in The Bulletin. On Our Selection comprised 16 chapters while On Our New Selection contained 14 episodes.

Davis wrote 24 books and six plays. Three silent and four sound-film adaptations ensued and there was a radio serial as well. Financially, Arthur did not make as much money as was warranted.

The following paragraphs from Good Old Bess (Chapter VI in On Our Selection ) demonstrate the style.

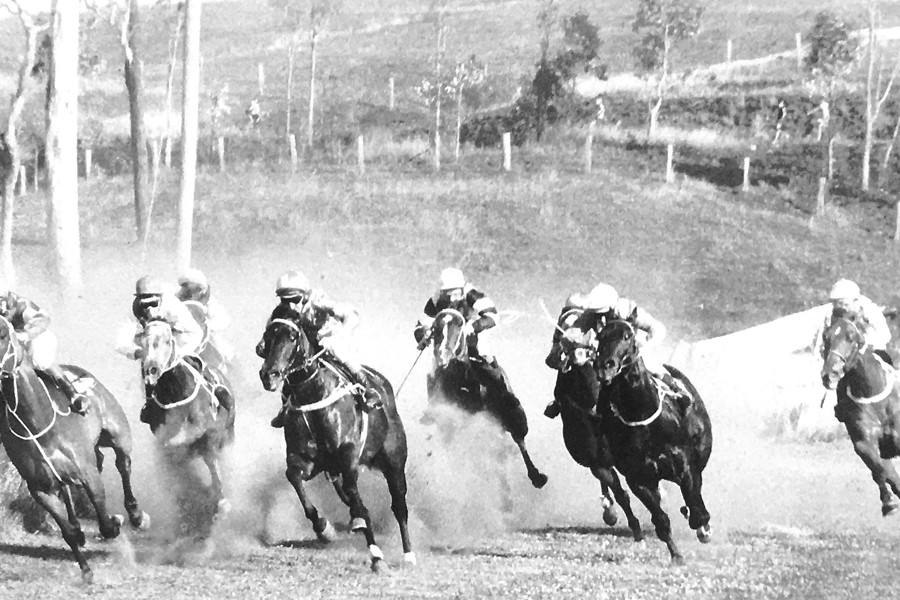

The gist of the yarn lies in the words: "Some horse races were being promoted by the shanty-keeper at the Overhaul, seven miles from our selection. They were the first of the kind held in the district, and the stake for the principal event was five pounds.”

“Dad stated that there’s great breeding in the old mare (Bess).”

The family really needed the money and so a serious preparation for the event kicked off.

“On the morning preceding the race Dad decided to send Bess over three miles to improve her wind. Dave took her to the crossing at the creek—supposed to be three miles from Single Hut, but it might have been four or it might have been five and there was a stony ridge on the way.

“We mounted the fence and waited. Tommy Wilkie came along riding a plough-horse. He waited too.”

Although Bart Cummings liked to get the mileage into the legs of his Cup prospects, Bess’s program would have staggered the Master.

A spoiler alert prevents the race result being disclosed.

Steele Rudd Park at East Greenmount features relevant historical buildings. Rudd’s Pub, established at Nobby in 1893, is described as being in the heart of Dad ‘n’ Dave country.

English-born Nathaniel (Nat) Gould (1857-1919) reached Brisbane in 1884, picking up shipping, business and turf assignments for Telegraph as well as representing The Sportsman.

Later he was editor for the Referee in Sydney, then held the same post at the Bathurst Times and reported on Carbine’s 1890 Melbourne Cup triumph.

His racing serials Blue and White and With The Tide entertained Australian and British readers. When Gould headed back to England in 1895 on the Orizaba, Carbine was a fellow voyager. The author of around 130 horse-racing novels was inducted into the Sport Australia Hall of Fame (Media) in 1989.

Major Oliver Hogue (1880-1919) was an Australian soldier and journalist who, under the "Trooper Bluegum” pen name, composed The Horses Stayed Behind. It was a sobering poem about the post-war fate of thousands of Light Horses.

In short, owing to quarantine rules and costs, the men were informed that their beloved Walers were not going home from Egypt and the Middle East.

Some steeds would be shot and assets such as shoes, mane, tail and hide would be cashed in. Some would live, only to be sold into dubious conditions. Bluegum’s sentiments, as shown below, were widely shared.

BEFORE THE BULLETIN

In 1934, Adam Lindsay Gordon (1833–1870) became the only Australian to have his bust placed in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey. He was born into a financially well-off situation in Gloucestershire. Apparently his parents Adam and Harriet were cousins.

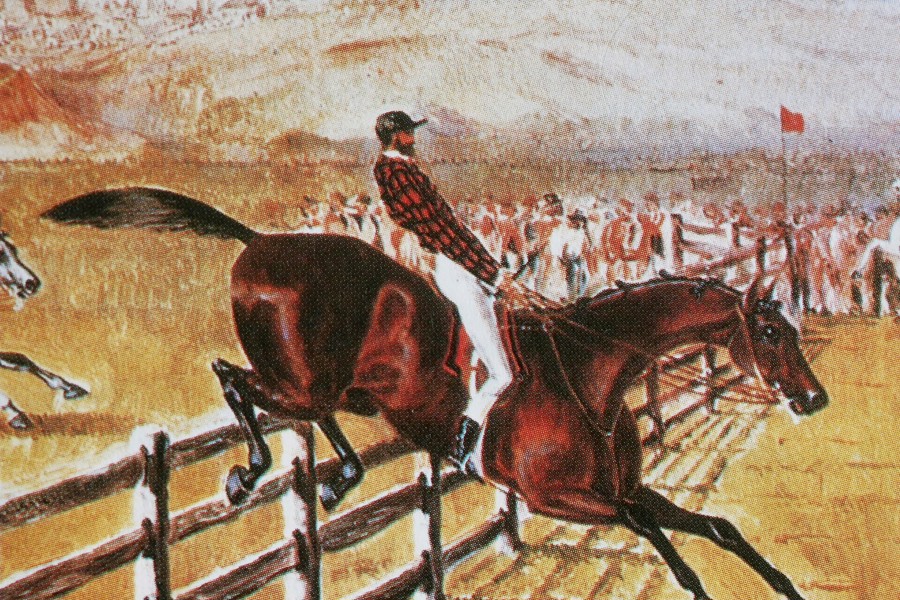

The well-educated 20-year-old emigrant was employed in 1853 by the South Australian Mounted Police before switching to horse-breaking and cutting his teeth as a steeplechase rider.

Despite his height and his need to wear his spectacles during jumps races, Adam had flair, nerve and technique, chalking up a treble over obstacles at Caulfield in October 1868. Although the area in front of his mount’s head was a blur, the story goes that he sensed when it was about to jump.

In 1864 Gordon, on Red Lancer, made an amazing leap over a high fence between Leg of Mutton Lake and the Blue Lake at Mount Gambier. The duo landed on a small 1.8m ledge with a 60m drop into the Blue Lake below.

Although he secured a seat in the South Australian parliament in 1865, he rode on and continued writing.

Hippodromania, a series in five discrete parts, contains individual epic poems about some Melbourne Cups of the 1860s. Gordon’s poetry was first printed in newspapers in 1864 and, in 1867, he published his first two volumes.

Trials and tribulations haunted him at times, particularly in his final years. After moving to Ballarat and joining the Light Horse, he was badly injured in a riding accident. The death of his infant daughter compounded matters as did his missing out an inheritance.

Even though his 1870 edition called Bush Ballads and Galloping Rhymes drew praise, it was soon after that Gordon went to Brighton Beach and shot himself.

MODERN TIMES

The Big Book Of Australian Racing Stories compiled by Jim Haynes in 2015 is an outstanding 586 page compendium of verse and prose, fiction and non-fiction.

There are entries for the aforementioned Paterson, Gordon, Gould, Dennis, Morant, Lawson as well as for Les Carlyon, Phil Purser, Mark Twain (with Cup Day is Supreme), Haynes himself and many others.

Betty Lane Holland, a trailblazer for female trainers, also contributed.

She had stints as the editor of the Australian Horse and Rider and editor of Hoofs and Horns (NSW edition) before she completely broke through racing’s gender ban.

After topping the Central Western Districts trainer’s premiership three times, she progressed to Randwick and became the first woman to be granted a Number 1 licence.

Her autobiography, I Did It My (Their) Way, was released in 2019.

And so to Rupert McCall, a genial genius who completes a ballad circle.

Kylie Knight (Quest News, March 18, 2018) wrote: “Discovering Banjo Paterson's magic at a small school in Woody Point introduced the young mind of Rupert McCall to a poetic rhythm which now beats in time with his own heart.

“It was 1980 and his Year 5 class at Our Lady of Lourdes Primary School was learning A Bush Christening by Paterson.

“I just thought that it was a pretty cool way of telling a story. It had the rhythm, it had a little bit of larrikinism, laughter. For me, it was like a jigsaw puzzle of words and putting the words together in a clever kind of way that ultimately came together and told a story.”

Rupert, who proudly lived in Redcliffe, penned his first poem in 1981. This dedication to trees was highly commended in an Arbor Day competition.

Seven years later, another effort won him a dozen home game tickets in a Radio Triple M contest to mark the Brisbane Broncos debut season in the Winfield Cup.

Super Impose’s 1991 Epsom triumph was celebrated in More Than A Horse when “like scissors through paper, they cut through the pack, and rapidly started to close”.

McCall’s also attended to Queensland’s signature race with:

“And I beg of you not to miss it, for to do so would be tragic,

It is something very special; It's a Stradbroke kind of magic”.

The former solicitor that became a multi-media identity delivered his 2013 piece about Black Caviar at Royal Ascot in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II. He has covered the Cox Plate and was the opening act in Channel Seven’s 2017 Melbourne Cup coverage. Of course, Winx has also been lauded.

McCall’s astonishing array of subjects and scenes includes reciting A Firefighter’s Dream during a Ground Zero ceremony in New York on September 11, 2010 and rendering 90 Years Ago at Anzac Cove in 2005.

The Australian-born Pulitzer Prize winning author Geraldine Brooks wrote Horse, an example of historical-fiction that scored four awards.

The former writer for the Sydney Morning Herald and the Wall Street Journal declared that the novel is a work of the imagination, but most of the details regarding the key character Lexington’s brilliant racing career and years at a stud are true. Many of the 575 foals he sired became outstanding champions, four of them winning the Belmont Stakes and three winning the Preakness and that Preakness himself was a Lexington foal.

Another form in this conversation is Free Verse. Life 1A and Life 1B represent the extremities of racing’s players.

THE FUTURE

Traditions are currently being sustained on several fronts. In Queensland alone this year, the Australian Bush Poets Association held events at Cloncurry, Winton, Boondooma and Kilkivan. September’s venues are Linville and Beenleigh.

Open and School level Bush Poetry performance contests were conducted at last month’s Brisbane Royal Show (aka Ekka).

In April next year at Corryong, “down by Kosciusko side” the 30th renewal of the Man From Snowy River Bush Festival will be staged.

Program elements over the three days embrace horses, cattle, cattle dogs, photography, art, poetry recitals, equine education and whip cracking.

It may well be short odds that a ten year old will have a crack after being inspired by the likes of Rupert McCall’s engaging repertoire.

Cultural enrichment will be regenerated. Just maybe, he or she will play a Banjo encore.